Years ago, a colleague shared this insight with me: “Everybody communicates, but not everybody is a communicator.” Her point was that anyone with the benefit of a primary education can string together words to form sentences and sentences to form paragraphs.

However, being a communications professional – like a journalist or an author – entails a much deeper and more subtle understanding of language and how an audience will respond to it. For example, an experienced writer might draw on a personal anecdote unrelated to their main subject to capture the reader’s imagination. I’m just saying.

With this in mind, I would like to offer my own corollary to her axiom. When anyone can purchase an extremely capable small uncrewed aircraft system (sUAS) – such as the recently released DJI Neo – for $200, it is reasonable to suggest: “Everybody aviates, but not everybody is an aviator.”

So, what distinguishes an aviator from somebody who aviates? More than anything else, I would argue that it is a professional mindset that always has safety as its top priority. However, beyond merely thinking “safety first,” this entails a systematic understanding of risk and how it can be mitigated through reasonable and appropriate precautions.

Cover image: Every remote pilot worthy of the title understands the need to fly safely, but true professionals understand how to systematically assess risk and document their safety procedures.

To Err is Human

Humans make mistakes. I make them all the time and, if you’re being honest, you do, too. Having accepted this as an established fact, the aviators among us will seek to reduce their mistakes to an absolute minimum. This is the goal behind one of aviation’s most fundamental risk-mitigation tools: the pre-flight checklist.

Let’s say you’re heading out to do some aerial photography. Essential to your success is the fact that there is sufficient storage space available on the memory card inside your aircraft to hold all of the imagery you intend to capture. How can you know for certain that is true? You could try to remember back to the last time you went flying, but the only way to be sure is to check the space available on the card.

Now, how can you make sure you do this before every single flight? You add it to your pre-flight checklist and you work your way through that checklist every single time before you begin a mission. How can you know for certain that your propellers aren’t chipped or cracked? How can you be sure that your aircraft batteries are fully charged? How can you know that the lens on your camera gimbal is clean?

You can believe something is true. You can hope something is true. Or, you can make sure that it is true through a systematic process of verification. Our sisters and brothers in the crewed aviation industry have been using this approach for decades because it works, and we would be foolish not to learn from their example.

Yet, here we must acknowledge they have a huge advantage over us. Every type-certified aircraft comes from the manufacturer with a flight manual and a detailed pre-flight checklist. If you buy an sUAS for $200 at the local big-box retailer, guess what? That vital document is nowhere to be found. So, it’s incumbent on us to develop and adhere to our own checklists.

Assessing Risk

The only way to eliminate all risk from flying is not to fly at all, and since that would deny us the immense benefits of both crewed and uncrewed aviation, that isn’t an option. Therefore, we must be prepared to accept some level of risk. But how much is too much?

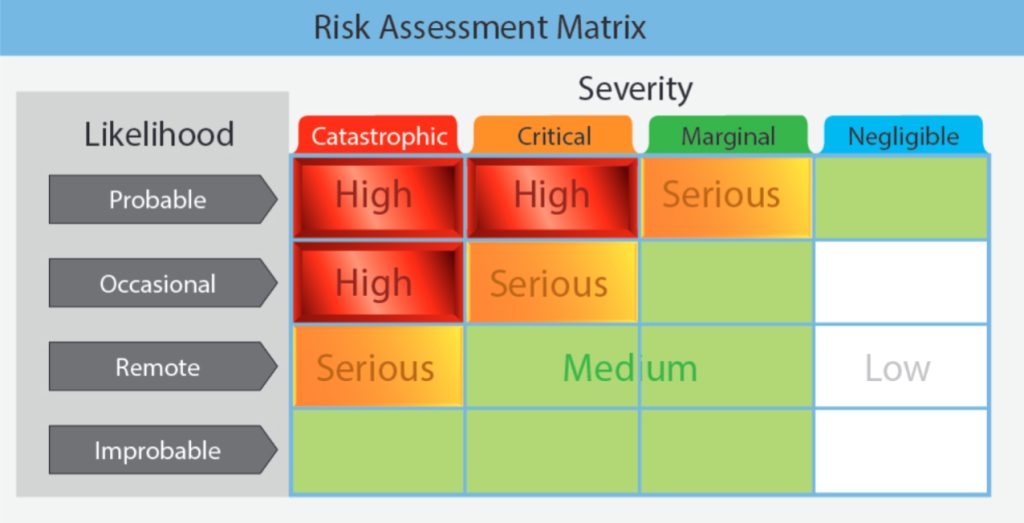

Aviators use tools like the risk matrix to assess the level of risk associated with a particular activity or flying environment and decide when it is okay to fly, when some sort of mitigation is required and when we should avoid flying altogether because the mission cannot be performed safely. Let’s begin with a low-risk example and see what the risk matrix can tell us.

One risk that all remote pilots face is the loss of communication with their aircraft – a so-called “lost link” incident. Now, with modern, commercially manufactured sUAS being flown within visual line of sight (VLOS), this doesn’t happen very often. Therefore, we judge the probability of such an incident to be “Remote.” It does occasionally happen, but not very often.

Next, we must consider the potential consequences of such an incident. Provided that our aircraft has good GPS reception and a solid fix on its return-to-home (RTH) location – both of those items are on your pre-flight checklist, right? – it should return to your immediate vicinity and even land itself if necessary. Given this fact, we judge the severity of this issue being “Negligible.”

Consulting the risk matrix, we discover that this is a “Low” risk eventuality so no mitigation is required.

Risky Business

Now, let’s crank it up a notch and see what happens. We are supporting a search-and-rescue mission in winter. Therefore, we will be flying in cold weather, which increases the internal resistance of lithium-polymer (LiPo) batteries and can cause abrupt drops in voltage and unreliable estimates of the power remaining. We judge that under these circumstances our aircraft might suffer a total loss of power “Occasionally.”

Next up, there will be search teams on foot moving through the area where we will be flying. Obviously, we’ll do our best not to fly directly over them, but we can’t guarantee that it won’t happen. Dropping an sUAS on somebody from a couple of hundred feet up could easily kill them, an outcome we judge to be “Catastrophic.”

The risk matrix reveals that the risk from this particular set of circumstances is “High,” which would be a no-go without some significant mitigation, such as rigging your aircraft with a parachute-based flight termination system. That might be sufficient to reduce the severity of such an incident to “Marginal” and thus reduce the risk to “Medium” – a much more favorable outcome for conducting flight operations.

The important thing to remember is that the risk matrix is just ink on a page. It doesn’t have any power apart from the power you give it: You can make it say anything you want. Therefore, it is incumbent on you to be honest, most especially with yourself, when using this tool to assess risk.

Onward and Upward

Checklists and a formal risk-assessment process may be sufficient for an individual operator. However, when your flight operations are occurring in the context of a larger organization, it is critical to consider that organization’s overall culture and tolerance for risk. Once again, the aviation community has developed a tool specifically to address this need: the Safety Management System (SMS).

While an SMS is far too complex to meaningfully examine here, it is universally described as resting on four pillars – Safety Policy, Risk Management, Safety Assurance and Safety Promotion – and underlying all of these is the concept of a Just Safety Culture.

When operating within a Just Safety Culture, pilots are expected to be fully honest and transparent regarding their mistakes, including mistakes with significant negative consequences for the organization as a whole. In return, the pilots will not face punitive measures for those mistakes. The premise is that it is better for everyone to learn from an open, honest discussion of errors than to have them remain hidden for fear of punishment.

Hopefully, you are beginning to get a sense of what it means to be an aviator, rather than a person who aviates. If you would like some help along this path, Women and Drones has partnered with the Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Office of Professional Education (OPE). It offers a variety of online four-week courses to help you develop a professional aviation mindset along with other skills to help you be successful. These courses can be strung together, allowing you to add a certificate from Embry-Riddle to your resume.

Best of all, each course sign-up through the Women and Drones landing page on Embry-Riddle’s website benefits the organization, helping support its mission of providing education and networking opportunities for women and girls in this fast-growing segment of the aviation industry.